One of the earliest contributions to the theory of nature of backwardness and the conditions for growth came from the Polish-born economist Paul Rosenstein Rodan as early as 1943, in the form of an article on the problems of industrialization in Eastern and Southern Europe.

In

this article and through later works, Rosenstein-Radon became a prominent

spokesman for massive industrial development as the way to growth and progress

for the backward areas, both on the European fringe and in the rest of the

world. Rosenstein-Rodan expressly distanced himself from neo-classical

economics and its static equilibrium analyses, and proposed instead that the

growth process must be understood as a series of dissimilar disequilibria.

In a paper from 1957, he expanded this argument further into a theory of the 'big push' as a precondition for growth. The background areas were characterised by low incomes and, therefore, little buying power. Furthermore, they were characterised by high unemployment and underemployment in agriculture. To break out of this mould, it was necessary to industrialise.

However, private

companies could not do this on their own, partly because they lacked incentives

to invest as long as the markets for their products remained small. The influence

of Adam smith's reasoning was apparent here but Rosenstein Rodan went further

with an identification of other growth impeding conditions, including the

companies' difficulties with internalising costs and consequently not being

paid for all the goods they produced, for example, the cost of training

workers who may then transfer their new skills to other companies.

Rosenstein-Roan

claimed that the barriers to growth could be overcome but this required active

state involvement in education of the workforce and in the planning and

organizing of large-scale investment programmes. And they had to be large scale

in order to set a self-perpetuating growth progress in motion, Rosenstein-Rodan

compared the 'big push' with an aeroplane's take-off from the runway. There is

a critical ground speed which must be passed before a craft can become

airborne. A similar condition applied to the growth process: launching a

country into self-sustaining growth required a critical mass of simultaneous

investments and other initiatives (cf. also Rosenstein-Rodan, 1984).

Ragnar

Nurkse took over and further developed many of Rosensteain-Roadan's major

points (Nurke, 1953). Nurke asserted that the economically backward countries

were caught in two interconnected vicious poverty circles, which can be

illustrated as in the figure.

The

reasoning behind the circles is that demand in backward countries is low as a

consequence of the very low incomes. When demand is low and the market limited,

there will not be much incentive to make private investments. Therefore,

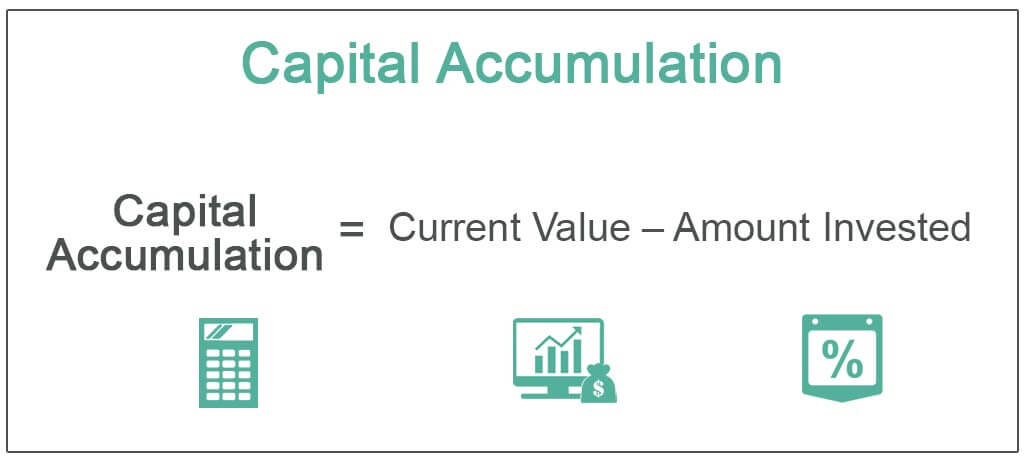

capital formation and accumulation remain at a very low level. As fore, remain

low. On the supply side, the low incomes result in a small productivity. The

final outcome is reproduction of mass poverty. Nurkse added to this that the

whole problem with attaining the necessary savings and capital investments was

compounded by rich people's tendency to copy, in their own consumption, the

consumption standards and patters of the industrially advanced countries. This

so-called Duisenberg effect implied an increase in the propensity to consume

and thus led to a reduction in the actual rate of saving.

The preconditions for breaking out of these poverty circles were, according to Nurkse, the creation of strong incentive to invest along with increased mobilization of invertible funds. This required a significant expansion of the market through simultaneous massive and balanced capital investments in a number of industrial sectors. This is dependent further on an actively intervening state, which could both plan investment programmes and ensure internal mobilization of resources. The state was important also to bring about optimal utilization of foreign aid, which Nurkse brought in as a critical strategy for initiating accumulation of capital on a grand scale.

It is important to note that behind both Rosenstein-Rodin's and Nurkse's modes of reasoning there lay a fundamental assumption that an increased supply of goods — as a consequence of capital accumulation — would create its own increased demand. Both theorists imagined that the market would expand as a consequent of increased capital investments which, in turn, would continue to grow in response to market incentives.

Comments

Post a Comment